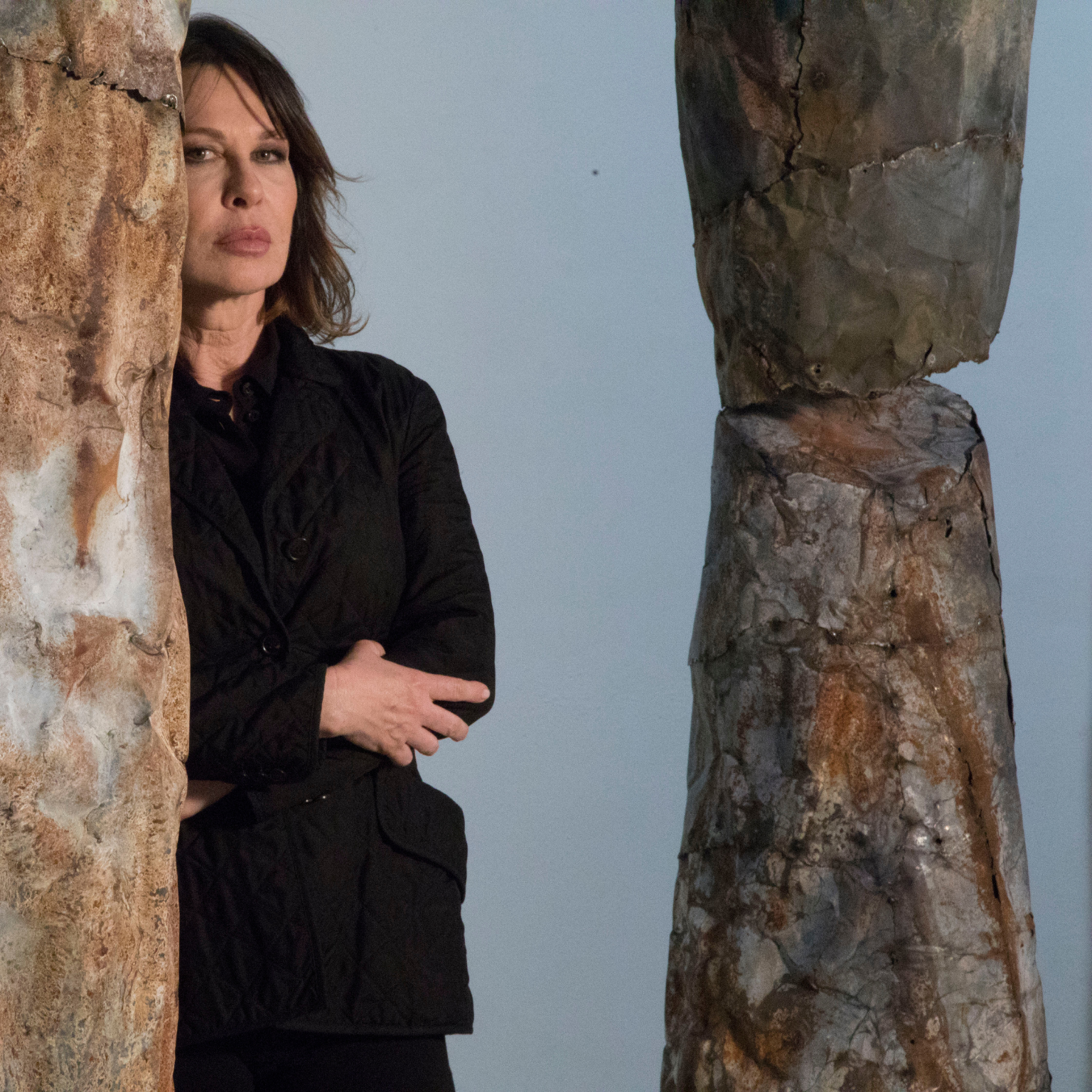

Francesca Leone, conceptual artist from Italy. Photo © Marco Palombi

This interview aligns with the ‘Nature and Culture’ Program initiated by the Culture For Causes Network. Within this framework, an exhibition titled ‘Reconciliation with the Living’ was exhibited in Paris at UNESCO HQ, focusing on the theme of harmonizing humanity with itself and the natural world; the exhibition travelled to Florence and Lisbon as well. Additionally, MuseumWeek 2023 featured numerous hashtags related to environmental topics, and a video series titled ‘Nature and Art’, a collaborative effort between UNESCO and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, was also showcased as part of this initiative. In 2024, more actions are expected to take place, including MuseumWeek 2024.

“About 15 years ago, I started giving a different value to abandoned things and my first exhibition on this theme was ‘Our Trash’ at the Milan Triennale”. Thus the contemporary artist Francesca Leone (Rome, 1964), through the use of different media including painting, sculpture, and installations, explores themes such as memory, identity, perception, and sustainability. She began her exhibition activity in 2007 with an exhibition at the Capitoline Museums and her works have been exhibited in various exhibitions and art galleries in Italy and abroad.

Daughter of art, her father is the great director Sergio Leone and her mother is Carla Ranaldi, the prima ballerina of the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, the works of the artist who graduated from the Rome University of Fine Arts in painting have been exhibited in Italy, but among others also in Singapore, Moscow, Madrid, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Santiago de Chile, at the MACBA – Museum of Contemporary Art in Buenos Aires and the Museum of the Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg.

In her conceptual and abstract production, Leone has trapped in some works objects that belonged to her family, in particular, her mother; a one-of-a-kind private collection to immortalize memories and gestures that cannot be forgotten. Objects given at the time.

In her studio in Rome, in this interview for MuseumWeek magazine, Francesca Leone tells us not only her passion for art and her innate talent but also some private anecdotes and how important sustainability is for each of us for future generations.

What did the Our Trash exhibition project at the Triennale in Milan consist of?

It consisted of a street made of grids in which I had trapped thousands of small objects: from cigarette butts to old photographs and receipts. The installation was on two levels, one more external with more current things and the other more internal with objects that are no longer used to underline the passage of time.

By walking on it, the project aimed to raise the viewer’s awareness of the importance of daily gestures that we could avoid because respect for nature and the environment depends on a small gesture. Furthermore, I was happy to see many students interacting with the installation.

From your point of view, what does the term “sustainability” mean?

“Sustainability” is giving new life to objects that are somehow thrown away, ruined, and have lost their function. Giving them a more poetic look like a rusty sheet of metal that perhaps covered a shack can become a rose, a flower, a drapery, it can look like paper.

I like working on this dual aspect. Now I’m working with sheet metal from abandoned construction sites and shacks: from rusty iron, they become something different. Behind all this there is naturally the desire to change things, to say: “We can do it!”.

Last year you were appointed Ambassador for Italy to the G20 in India…

When they asked me to present a project, I thought of Una rosa, è una rosa, è una rosa (A rose, it’s a rose, it’s a rose. Editor’s note: about the meaning of the words of the writer Gertrude Stein in her poem Sacred Emily, 1913).

They are three roses of different colors: one rose was completely painted to cover the rust and the holes, the second still had some rust residues where you could see the wear and the passage of time, and finally the third was completely rusted, so there was no absolutely my intervention. Precisely this last phase makes us understand that we can all do something, we must do something to change the future.

Could we also interpret this process in general as the three phases of life?

Certain! There is youth, maturity, and then old age. But about the environment, my message is to take care of it for future generations and think about what we leave to them. I don’t have children, so I don’t have this burden, but if I had, I would certainly be very worried today.

What is the role of the artist in this aspect?

Some artists feel politics in art and talk about their time, their scars, and their pain. On the other hand, I am sensitive to the issue of the environment, and I started dealing with it when it was not yet so evident, but I am not sensitive to the political one. The artist is far-sighted thanks to his sensitivity. Politics and life make you short-sighted and we can all talk about it, but we need to take action. Do something.

Let’s say that the power to make money does not very often marry with nature. We don’t realize that we are destroying something that belongs to us: the future. I recently saw a documentary in which it seems that in about ten years the sea can be cleaned up thanks to large ships. Let’s hope this is the case!

What material do you prefer for your work?

The material that I love very much in this period is sheet metal because it allows me to make both sculptures and hanging works that almost look like fabrics or stalactites. Recycled metal sheets, welded, stitched, and repainted, give me a feeling of lightness. In the beginning, I framed the material and then little by little I freed it because it’s nice to see it breathe.

An example of this is Take Your Time, a collateral event that I did during the 59th Venice Biennale. The title of the exhibition comes from a post-Coronavirus pandemic reflection: there were five rooms and in each, there was a world to enter, and take your time to observe it and meditate. The virus forced us to stay indoors and this hurt us, but also good from a certain point of view.

In what sense? Why?

Because it gave us the chance to stop and reflect on our lives. Today we are overwhelmed by true or false images and news, by routine, by the daily rush, by power, but we don’t have the time to think about what we want. After the Coronavirus I met many people who abandoned their jobs to do what made them feel better. The pandemic was good for some people, and it was also good for nature: we saw the seas clean, and the animals regain possession of their spaces.

Let’s say that man is the most wicked and least far-sighted animal there is. He is convinced that he is very intelligent, but for me, he is not at all because man’s nature is greedy, he is selfish. He is not very empathetic towards his fellow men and animals. Empathy is very important, however, and if you don’t have it towards what doesn’t belong to you, you can’t understand.

Speaking of the future: young people and the environment. How do you consider the new generations?

I see many young people who are more educated than us in thinking about the environment. I thought a lot about the Swedish activist Greta Thunberg because it was said that she was manipulated and constructed, but even if it was her, who cares? Her message is positive and right that she is arriving and has reached young people.

The fault lies not with young people, but with previous generations because many have criticized it and this is dramatic. In my works, there is a positive glimmer because there is the desire to recreate something beautiful from something dead. There is a message of rebirth, so my hope, even if it is not easy, I always have it.

Changing the subject, you have an important surname, how much has it influenced your artistic career?

I had to work harder. My last name made me recognizable in one way, but I also noticed that people could be prejudiced without seeing my art. Then luckily, seeing my production and my path, they changed their minds. Maybe with a stage name, it would have been a simpler path.

What kind of person was your father, the director Sergio Leone?

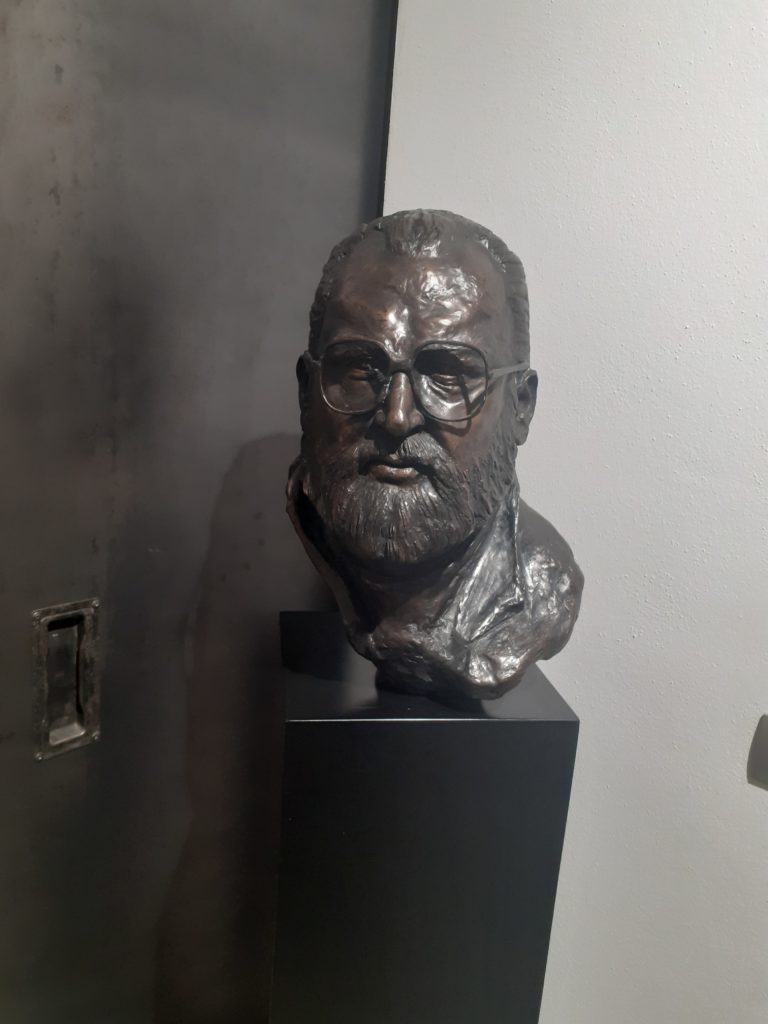

My father was an authoritative person but also very nice and funny, two opposite sides, but with a thousand facets. He was very rich inside, with a thousand interests and curiosities that he passed on to me. This is a wonderful legacy. My father passed away when I was very young, but I remember that when I was little I made a small sculpture of him and then in his art collection at home he hung a drawing that I had made of him with his crew.

He had seen this innate artistic streak in me and if I hadn’t been an artist as a job, I would have done it for myself because art helped me and made me feel good. It gives me the chance to express myself. I miss my father in all facets of life. It pains me not to let him see what I have done and not to be able to share all this with him.

When he was here, his work took him away from me for months and as a daughter, there was also a bit of jealousy, but today doing this job I realized that an artist is completely absorbed in his work, so today I understand more. I understand his distance, very often he wasn’t there, and he was very focused on himself a son doesn’t understand many things at the moment and sees them as something that your father takes away from you, but in reality, he couldn’t have done otherwise.

© Fabio Pariante, Francesca Leone’s Studio, Rome, 2023

In your production, there is a series of giant portraits, one of which is dedicated to Maestro Ennio Morricone who worked with your father. You presented it on the occasion of the “Mc Kim 2009” Award of the American Academy in Rome. Can you tell us about this experience?

The giant portraits are part of my first works, those dedicated to the heroes of our time who spoke of peace and inclusiveness among peoples, from Gandhi to Martin Luther King, but before that, I had portrayed my family. Very fast, strong, and vague brushstrokes in which the further you moved away, the more you perceived the image and if you moved away you lost it.

The portrait I made of Ennio was presented during the event and he was so happy that to reciprocate my gesture, he dedicated to me one of his compositions entitled Jerusalem, which was played for the first time in Rovereto in a wonderful setting. It is some of the most difficult music of his production and I remember that when he invited me to listen to it he was very worried, he told me: “It’s not like the ones I make for films…”, he was worried that I wouldn’t like it.

Here is the humility of the great; he was a sincere person and if he liked you as a person he showed it to you. He was a very lovely person and was happy to see me every time.

Interview by Fabio Pariante, X • Instagram • Website